The accuracy of the Seekr Score is continuously

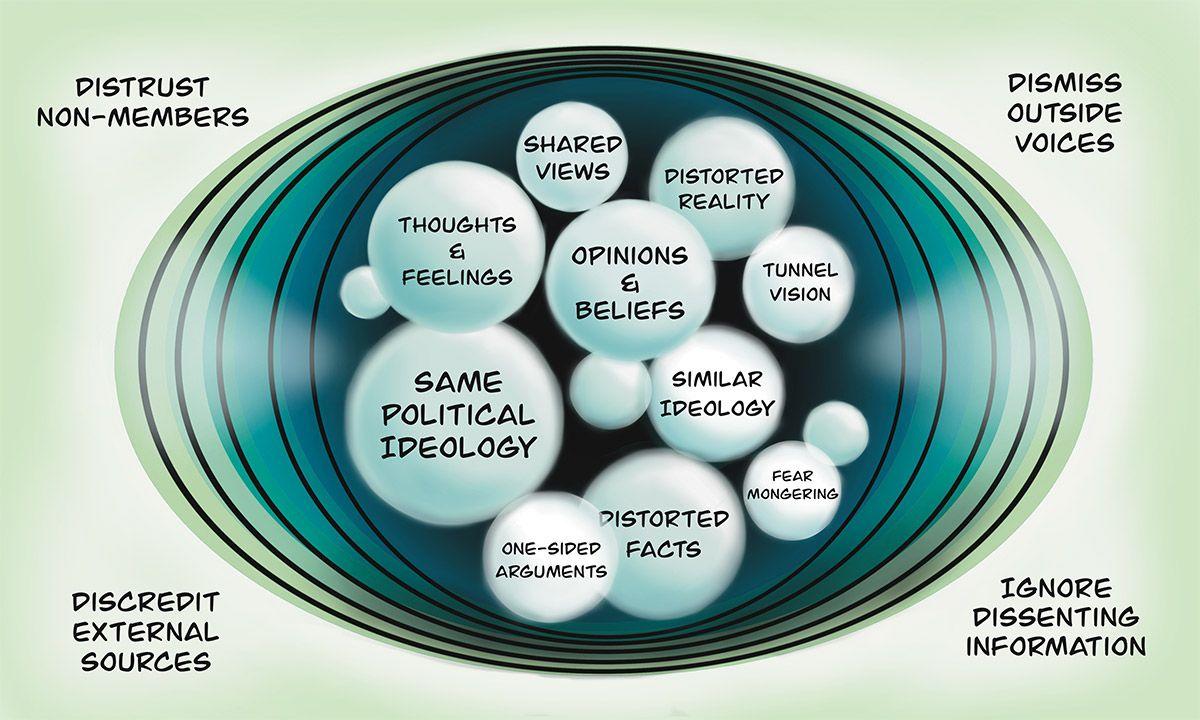

It might not be evident, but we are all operating in some sort of filter bubble. Like the saying about living inside a bubble, which means people don’t understand anything outside of it, a filter bubble is a group we live in online, in our digital and social media interactions. It’s where we end up, unintentionally, with like-minded people. Being trapped in these boundaries can lead us to make poor decisions and cause harm.

Contrary to what the world feels like right now, Rutger Bergman lays out in his book Humankind: A Hopeful History that humans, by nature, are friendly and want to get along and cooperate. Bergman’s book has made waves as being radical. But his claims make sense. We like to get along. We like when people agree with us. It makes us feel like we are connected and belong with each other.

Having a tribe to call our own makes us happy. And to stay in that tribe, we spend much time trying to fit in, keep up with the Joneses, stay relevant, and not lose. Some of us might have extreme FOMO, some not. But no one likes feeling left out. We are social creatures, and we like having friends. And everyone wants to be liked.

When Facebook first took off in the early 2000s, it was the trendy new hangout where people connected with new, old, and forgotten friends. If you weren’t around then, were shy of it, or don’t remember, Facebook existed to share what was happening in our lives, post photos (not even of ourselves!), and share good times.

When it came to news, at that time, if we were interested, we got our news from newspapers, TV, and radio, and no matter what the story, we didn’t have the option of a Like button. If we didn’t like it, we yelled at the TV. And if we did like it, we didn’t have a way of sharing it with many people. Our views were shared over lunch, and more heated debates may have been reserved for after-work drinks.

Fast forward to 13 years past the activation of the Like button, and 40% of Americans between 18-40 read news on Facebook. According to a 2021 Pew research study on news consumption across social media, nearly half of Americans get their news from social media.

Now everyone's thoughts on anything from court drama news to heart-string-tugging news to bad-service-at-a-local-restaurant news are validated with likes and shares, algorithmically multiplied, promoted, and promoted some more.

Herein lies the basis of our problem. We were once passive news consumers, but as active digital news consumers, we click on the news we want versus the information we need. We desperately need the truth, but the news we receive is often far from it. Add to that being trapped in our filter bubble, and it’s an echo chamber where our views are parroted back to us. So, when the tiniest bit of false information starts circulating, it just takes one bad apple to spoil the bunch.

Ask yourself if you’re in a filter bubble. Is it clear to you? Does everyone around you share similar views? Here’s an experiment: Ask someone you know well to see their social media feed. Would you ever think to ask to look at someone else’s social media feed with views you disagree with? If you know someone like that, try it out and see what you see.

It’s only human to be afflicted with confirmation bias, the psychological term for when we focus on what confirms our beliefs and ignore views that contradict them. And once we identify that we have confirmation biases, we can work to break free from them.

What makes News the News?

In Journalism 101, students learn what gives news its news value. Several characteristics, like relevance, novelty, timeliness, level of conflict, etc., provide a story its news value. Today, shareability is the main characteristic that differs between online news and past news formats. The pressure for clicks and shares has become the internet’s top priority.

Social media, as it was established, was about sharing. Ordinary people have become news producers, and it’s no different; they also want engagement, and algorithms will promote that. Australian communications and media scholar Axel Bruns created the phrase Produsage: When the internet users produce the product they once consumed, whether it’s open source software, TikTok videos, or a blog. Since the produsers are likelier to share content that creates a shock or is emotional, spreading misinformation has a snowball effect. See the equation below that demonstrates this:

(Echo Chambers & Polarization) + (‘Produsage’ Phenomenon) = Misinformation Petri Dish

The consequences of this petri dish have not been undocumented. It’s been two years since the release of the Social Dilemma documentary on Netflix, and one year since Frances Haugen’s whistleblower testimony against Facebook, saying the company prioritizes growth and profits over the wellbeing of children and our democracy. We know the adverse effects of excessive social media use: addiction, mental health issues, extremist views, isolation, polarization, and more. But what can we do about it?

Try to rewrite the calculation above to find a healthier equation.

(Burst your bubble) + (Verify the Sources of your news) = Get a Handle on Misinformation

Many other variables can add up to becoming more media literate online. This blog and our work at Seekr try to solve the problem by tackling as many variables as possible. But no matter how we mix up the equation, know that the responsibility is individual; You always have a choice.